Liveable Dublin

Dublin City Council have resurfaced plans to turn College Green into a central plaza, but is pedestrianisation enough to make Ireland’s capital genuinely liveable?

Hannah Weir shows that Dublin needs to prioritise housing above all else to ensure the city is a welcome and sustainable place.

7 min. read

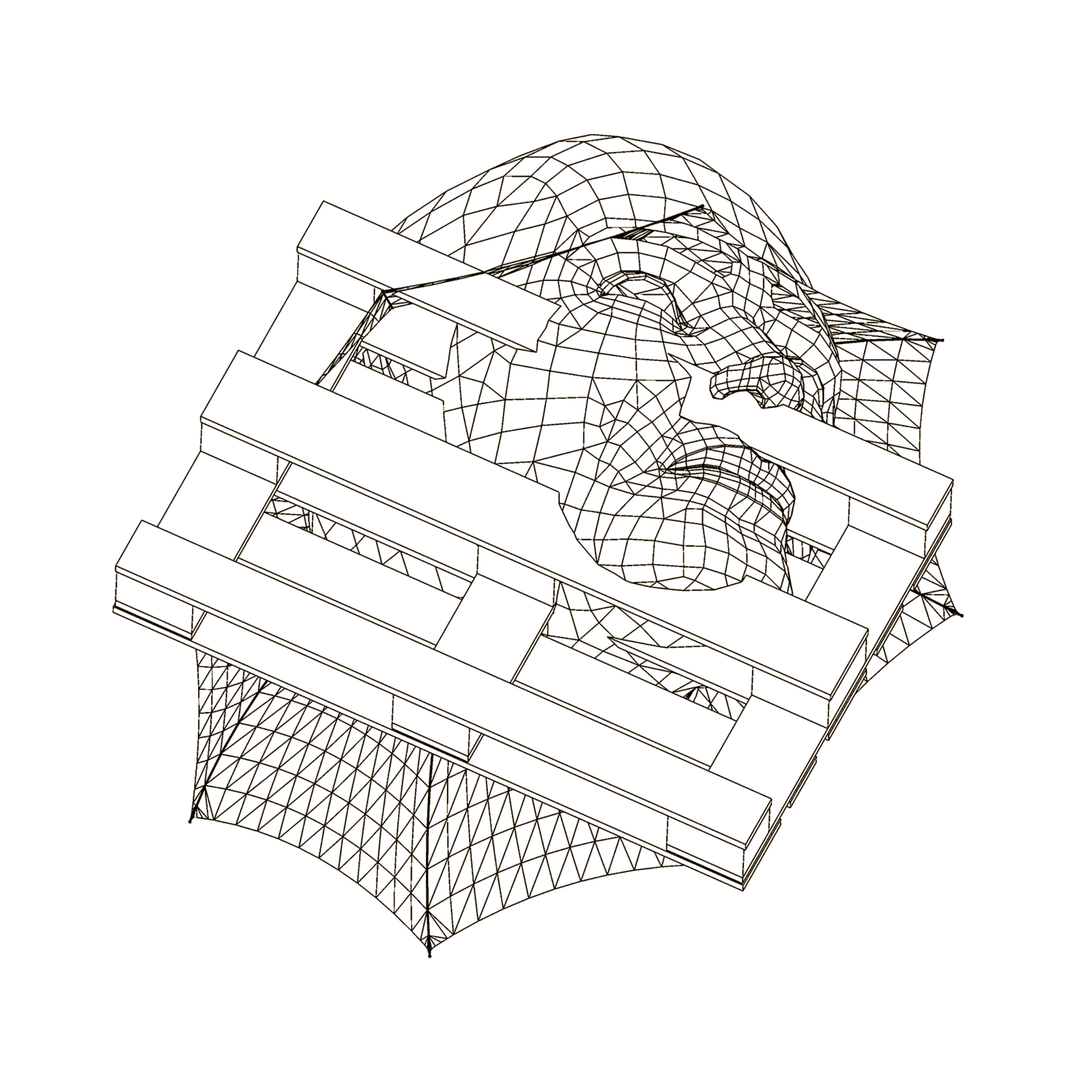

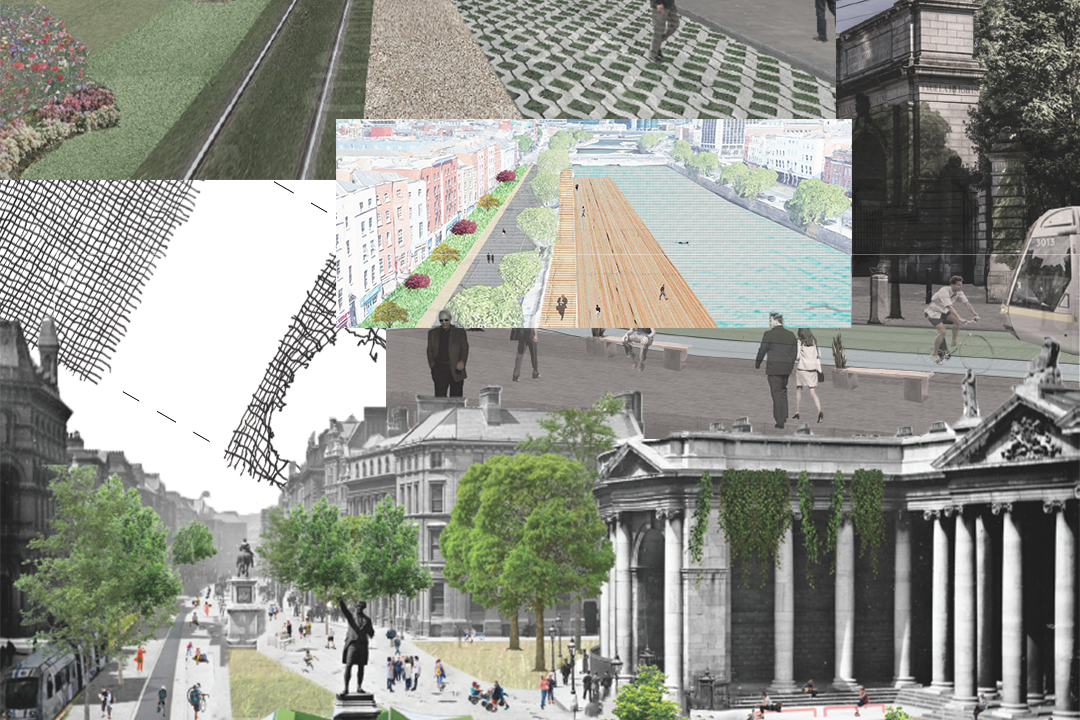

As Dublin and the rest of Ireland attempt to navigate the ebbs and flows of COVID restrictions, Dublin City Council’s published plan to pedestrianise College Green and turn it into a central plaza garnered much praise, similar to other short-term pedestrianisation projects seen on South Anne Street. Pedestrianisation projects in high footfall areas are far from unworthy projects for any capital city’s council. They will add much to the look and feel of the city centre. The issue here is that we are all too painfully aware of how Dublin’s problems require a lot more than the most central point of the entire region getting a facelift. It does little by way of making Dublin a liveable city, one that is more equipped at providing for its long term residents rather than panders to its tourists. The housing market would be a good place to start.

In April 2019, an exhibition entitled ‘The Vienna Model – Housing for the 21st Century’ was launched in CHQ in the Dublin docklands. It’s slightly ironic that an exhibition outlining how two-thirds of Vienna’s population lives in state-implemented and subsidised housing schemes would be launched in the very district of Dublin which symbolises to many all the processes that have caused Dublin’s current dire housing situation.

Wohnpark Alterlaa / Social Housing in Vienna

Vienna’s plan was very much tried and tested when it came to the Great Recession that began in 2008. Austria’s reaction to the crash was incredibly stable. House prices did not fluctuate and social housing output was relatively fixed, even through the worst years of the economic downturn. The social housing portion of the market is essentially what kept Austria afloat. The sheer supply of public housing that was built separately from the private housing stock ensured Austria had a short and relatively painless recession by multiple accounts.

The biggest barrier to Dublin having this same rate of success is unfortunately tied-up in multiple overlapping policy decisions stretching from fifty years ago. Dublin’s public housing assets were crippled by past policies of allowing council housing tenants the opportunity to buy their dwellings, and subsequent lack of maintenance on the public stock that remained, compounded the fact that these houses that were sold were never replaced at the same volume.

It seems suspiciously too easy that the solution would be to say, “we just need to build more houses” and whilst this isn’t necessarily untrue, it isn’t reflective of reality. The increased output of social housing in Dublin’s case is reliant on three factors: land, construction costs, and regulations. The city council sold vast acres of public land by the end of the last century, limiting the space that could be used to hold anything of public interest, let alone enough living spaces to rectify the current problem.

A central factor in determining the break-even rent is the cost of construction per square metre. The hourly wages paid to construction workers, the need for each apartment in a block to have its own car-parking space according to regulation, means Ireland’s construction costs are much higher than our European counterparts. The overall cost of construction demonstrates there would need to be a serious commitment by any current or future administration to completing these projects, lest there be a repeat of the empty shells left by the previous crisis.

Social Housing In Vienna

Ireland’s prominent home-ownership culture has meant the rights of renters have long been forgotten, and the rights of those actually owning the properties brought to the forefront. Austria’s well established rental culture has allowed for renting long-term without insecurity and stress that we associate with renting here in Ireland. Rents in Vienna do not include a profit margin; the money you pay each month goes towards the ongoing cost of the maintenance of the building where you live, limiting the risk of one-bed apartments going for upwards of €2,000 a month that we’ve become all too used to. The safety net of housing subsidy for those who may not be able to afford it is also incredibly well-enforced.

The Ballymun flats were just one example of how Dublin didn’t know it had a good thing until it was gone; once a shining example to other cities of how to house your citizens. A state of the art housing development of the 1960s that fell into disrepair and abandonment, with those who could afford to move to another area with more amenities and resources doing so. Fixing Ireland’s housing goes beyond mere bricks and mortar but rooting physical spaces and shells with the fundamentals of community spirit. Ballymun was severely impacted by the lack of fundamental amenities needed to build community relations - from a pragmatic and social level. The area was bereft of schooling, banks, shops, community hubs until much later into its lifespan. We see time and time again how the liveability of this city comes up against an almost primal desire to amplify neoliberal corporatist interests at all costs. Recent examples such as the backlash from the O'Devaney Gardens redevelopment in Dublin 7 show us how creating houses without the fabric of communities kept high on the priority list does not solve the problem, but pushes it to another postcode.

The issue with implementing anything anywhere near the Vienna model comes with the caveat of time. Where Vienna and other cities like it have spent the last decades reinforcing layers and layers of protection on a well-established housing system, Dublin has spent that same amount of time opening the doors to forces that are tearing down its own. Even if we find the land to build the houses, allow for taller buildings, subsidise the cost of construction, make it more secure to rent amongst a dozen other large-scale changes, time and consistent policy vision appears to be the only real remedy.

It makes perfect sense to build Dublin’s social housing inventory into one similar to the Viennese model, but governing practices of the past did little to ensure sustainable public housing policy could be pursued then, or by any administration in the future. With the waiting list for social housing currently standing at around 7 years, Dublin City Council has a more pressing issue to attend to if they wish to give the impression of a city fit for purpose in the 21st century — giving residents the means to forge a life, as opposed to simply beautifying the city centre, would be a meaningful start.

Hannah Weir

We value original, substantive ideas – mainstream or alternative, progressive or conservative – and encourage everyone to join our discussion.

content@facmagazine.com